Does everything revolve around you?

Look up at the sky at night and it is easy to imagine Earth is the center of everything. The stars and planets move in predictable cycles, while the ground beneath our feet feels motionless.

Until the 1500s, almost everyone believed in the ancient concept that Earth stood still and the heavens moved around it. Many believed the Bible also supported this view. However, the work of Polish cleric and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus began to change opinions, helping ignite a scientific revolution.

“He set the earth on its foundations, so that it should never be moved.”

Psalm 104:5

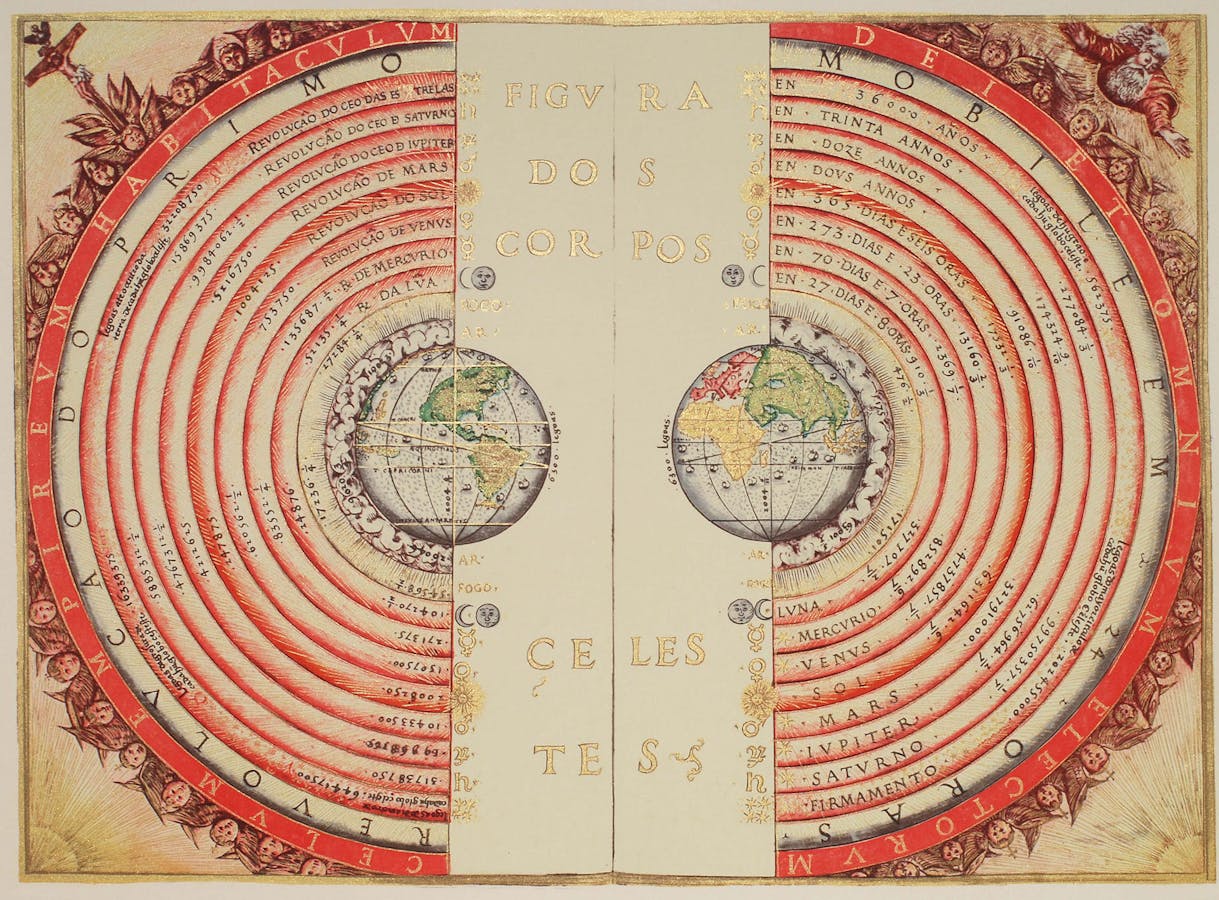

Nicolaus Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres helped to spark the Scientific Revolution. In 1616, the Catholic Church placed it on the index of prohibited books until certain passages about heliocentrism were censored.

Image courtesy of the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Copernicus was a well-versed scholar and church canon before turning to astronomy in the early 1500s. He became dissatisfied with the prevailing model of the heavens, which led him to question the idea that everything revolved around Earth, known as the “Ptolemaic model.” He eventually proposed his own “heliocentric,” or “sun-centered,” theory.

Copernicus was reluctant to publish his theory, however, partly fearing ridicule because a moving Earth seemed absurd. It was not until 1543, when he was on his deathbed, that his great work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolutions of the heavenly spheres) was finally published.

Copernicus’s theory did not receive the level of criticism he feared. In fact, both scientific and religious leaders, including the pope, had urged him to publish it. But while supporters found it interesting, most did not believe this new “Copernican system” was literally true.

Why were people skeptical? The theory contradicted established physics as well as common sense. It also contradicted the way many people understood the Bible, especially passages such as Psalm 104 and Joshua 10. It would take another century, and new evidence, before the Ptolemaic model was overturned, which in turn helped theologians better understand the Bible.

“The motions of the world machine” were “created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all.”

Nicholas Copernicus, De revolutionibus, 1543

Did Copernicus’s theory demote the importance of humanity in the cosmos by making the sun, rather than Earth, the center of the universe? While some modern authors have claimed this, it has no historical basis.

At the time, it was not human vanity that placed Earth at the center of the cosmos. The Earth was at the lowest level of the cosmos because it was thought of as a place of change and corruption, while the heavens were eternal and unchanging.

Nicolaus Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres helped to spark the Scientific Revolution. In 1616, the Catholic Church placed it on the index of prohibited books until certain passages about heliocentrism were censored.

Image courtesy of the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Copernicus was a well-versed scholar and church canon before turning to astronomy in the early 1500s. He became dissatisfied with the prevailing model of the heavens, which led him to question the idea that everything revolved around Earth, known as the “Ptolemaic model.” He eventually proposed his own “heliocentric,” or “sun-centered,” theory.

Copernicus was reluctant to publish his theory, however, partly fearing ridicule because a moving Earth seemed absurd. It was not until 1543, when he was on his deathbed, that his great work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolutions of the heavenly spheres) was finally published.

Copernicus’s theory did not receive the level of criticism he feared. In fact, both scientific and religious leaders, including the pope, had urged him to publish it. But while supporters found it interesting, most did not believe this new “Copernican system” was literally true.

Why were people skeptical? The theory contradicted established physics as well as common sense. It also contradicted the way many people understood the Bible, especially passages such as Psalm 104 and Joshua 10. It would take another century, and new evidence, before the Ptolemaic model was overturned, which in turn helped theologians better understand the Bible.

“The motions of the world machine” were “created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all.”

Nicholas Copernicus, De revolutionibus, 1543

Did Copernicus’s theory demote the importance of humanity in the cosmos by making the sun, rather than Earth, the center of the universe? While some modern authors have claimed this, it has no historical basis.

At the time, it was not human vanity that placed Earth at the center of the cosmos. The Earth was at the lowest level of the cosmos because it was thought of as a place of change and corruption, while the heavens were eternal and unchanging.

Nicolaus Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres helped to spark the Scientific Revolution. In 1616, the Catholic Church placed it on the index of prohibited books until certain passages about heliocentrism were censored.

Image courtesy of the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Copernicus was a well-versed scholar and church canon before turning to astronomy in the early 1500s. He became dissatisfied with the prevailing model of the heavens, which led him to question the idea that everything revolved around Earth, known as the “Ptolemaic model.” He eventually proposed his own “heliocentric,” or “sun-centered,” theory.

Copernicus was reluctant to publish his theory, however, partly fearing ridicule because a moving Earth seemed absurd. It was not until 1543, when he was on his deathbed, that his great work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolutions of the heavenly spheres) was finally published.

Copernicus’s theory did not receive the level of criticism he feared. In fact, both scientific and religious leaders, including the pope, had urged him to publish it. But while supporters found it interesting, most did not believe this new “Copernican system” was literally true.

Why were people skeptical? The theory contradicted established physics as well as common sense. It also contradicted the way many people understood the Bible, especially passages such as Psalm 104 and Joshua 10. It would take another century, and new evidence, before the Ptolemaic model was overturned, which in turn helped theologians better understand the Bible.

“The motions of the world machine” were “created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all.”

Nicholas Copernicus, De revolutionibus, 1543

Did Copernicus’s theory demote the importance of humanity in the cosmos by making the sun, rather than Earth, the center of the universe? While some modern authors have claimed this, it has no historical basis.

At the time, it was not human vanity that placed Earth at the center of the cosmos. The Earth was at the lowest level of the cosmos because it was thought of as a place of change and corruption, while the heavens were eternal and unchanging.