Perhaps no mystery has been more puzzling than the origin of life. How did life begin?

For centuries, many scholars embraced the idea that natural processes, including the idea of “spontaneous generation,” could explain the origin of some forms of life. This theory proposed that non-living materials could spontaneously generate living things, which some believed was consistent with the biblical account. In the seventeenth century, scientific advances challenged this idea.

Today, there is no scientific consensus about life’s origin. Yet, most scientists recognize the remarkably complex conditions needed for life to arise. Some claim this complexity requires a creator.

“Man’s first look at the universe discovers only variety, diversity, the multiplicity of phenomena. Let that gaze be enlightened by science—by science which draws man closer to God—and simplicity and unity shine forth everywhere.”

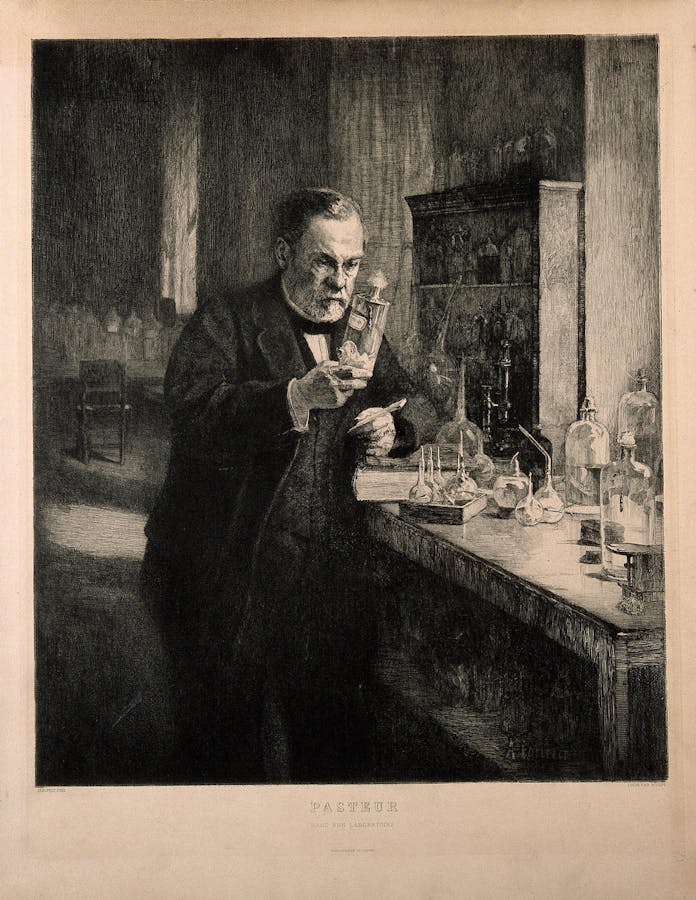

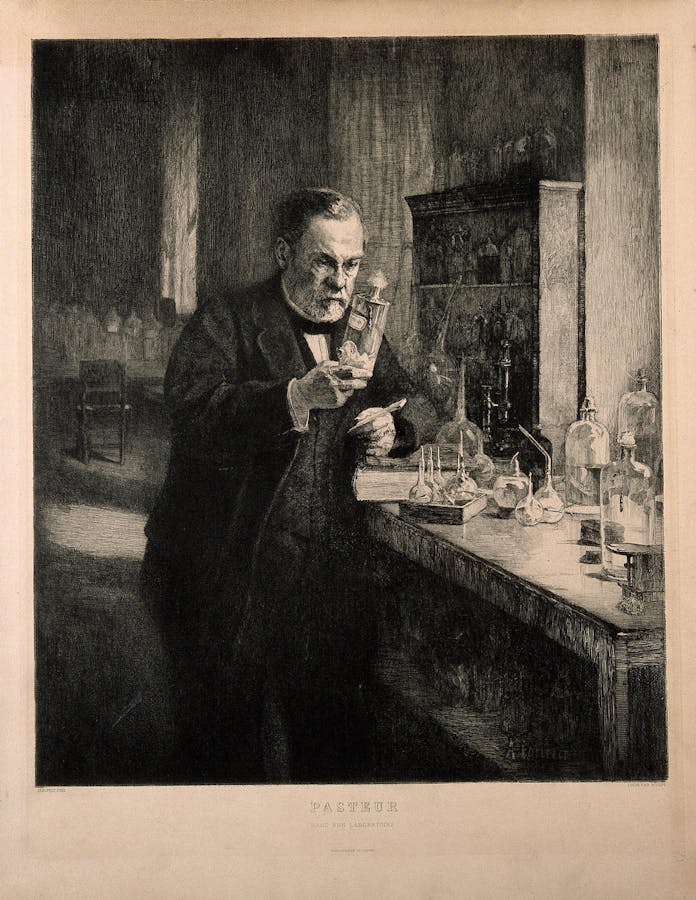

Louis Pasteur, ca. 1863

Can life arise from non-living things, driven by mere chemical reactions?

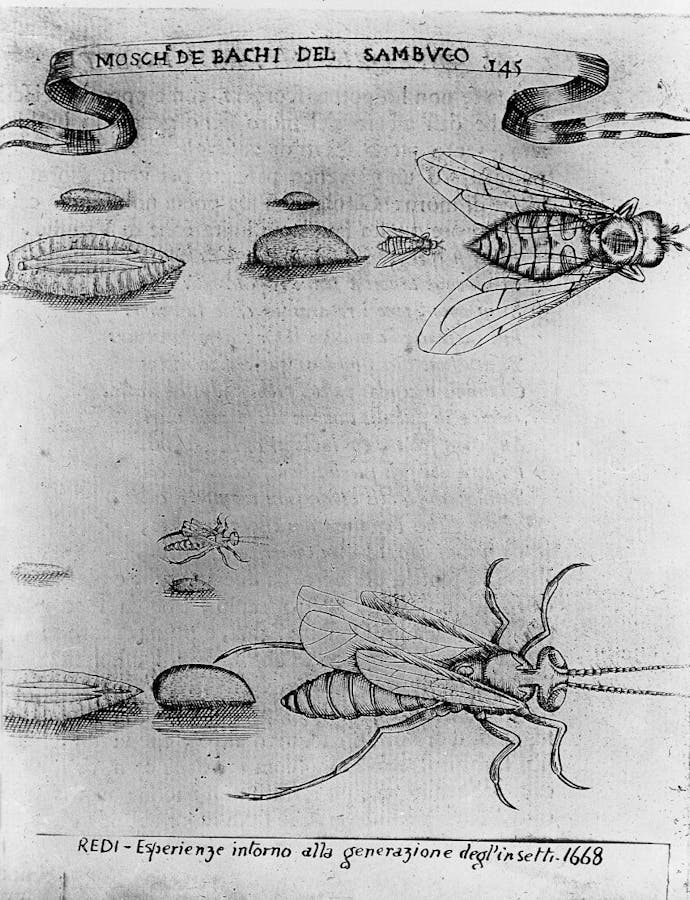

Until the 1600s, most natural philosophers and theologians assumed that at least some forms of life could “spontaneously generate” from non-living material. Francesco Redi, a Catholic physician and naturalist, challenged the view through a ground-breaking experiment proving maggots came from fly eggs too small to see.

Redi summarized his experiments with the phrase, “All life is from life.” His work ignited a long debate over spontaneous generation that was partially settled by the work of French Catholic chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur.

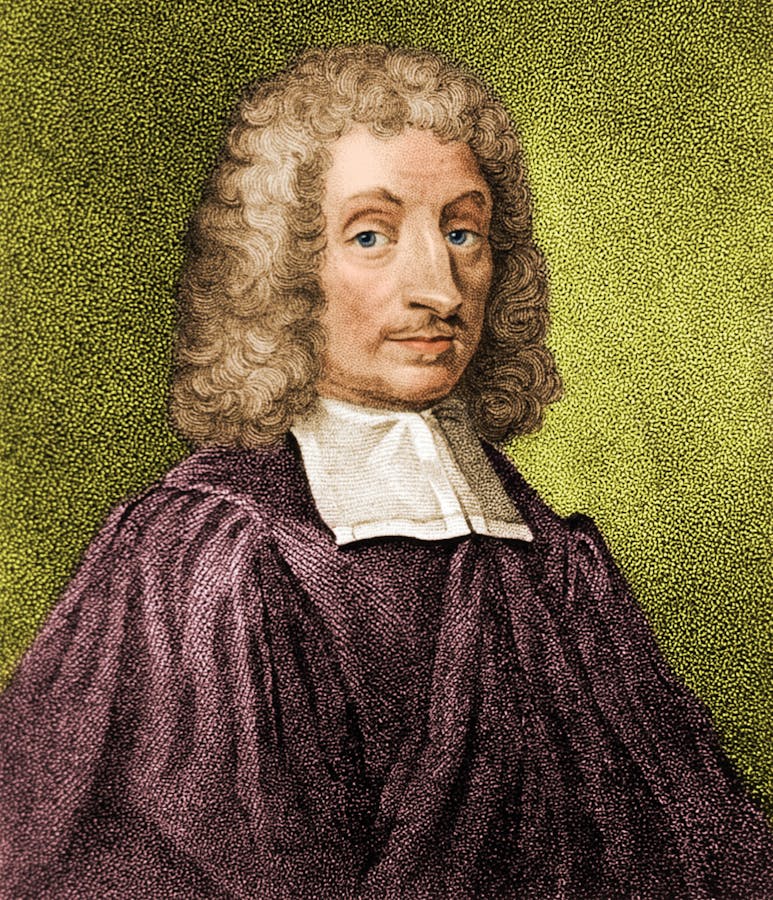

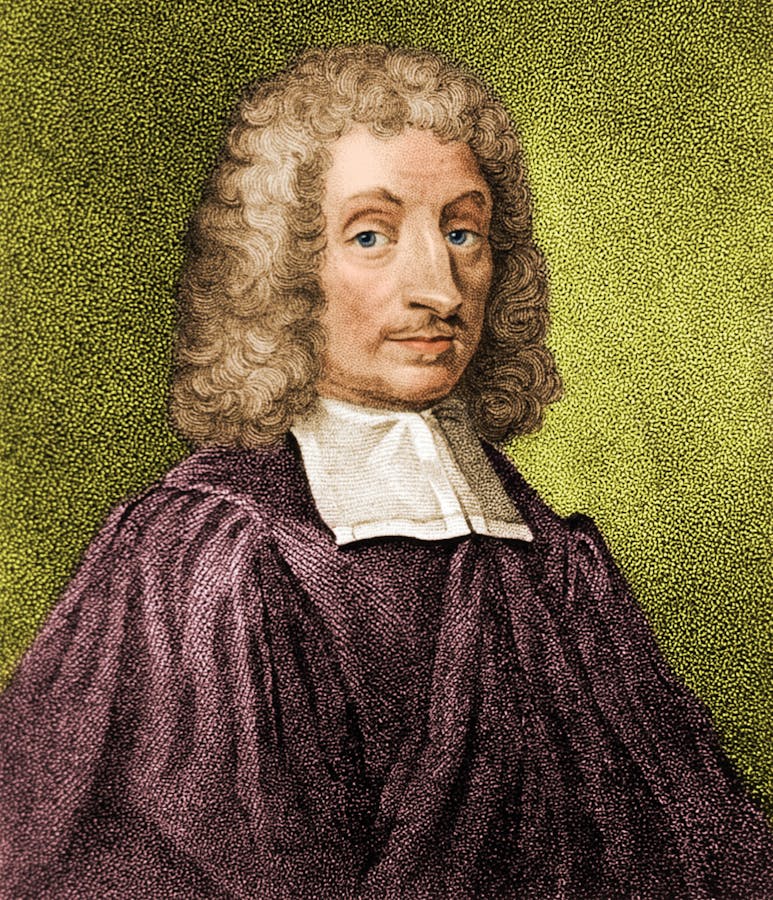

John Ray, depicted in this portrait, aided in laying the foundations for taxonomy, which is the scientific way of classifying organisms: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species, best remembered as Kevin’s Poor Cow Only Feels Good Sometimes.

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

John Needham’s experiments extended beyond mutton broth. In 1745, his study on blighted wheat revealed microscopic organisms he dubbed “eels,” (figure 6) since they looked similar and appeared to thrive in freshwater.

J. T. Needham, an account of some new microsc. Wellcome Collection.

A portrait of Lazzaro Spallanzani is surrounded by specimens he experimented on, such as the frog, and scientific equipment.

The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

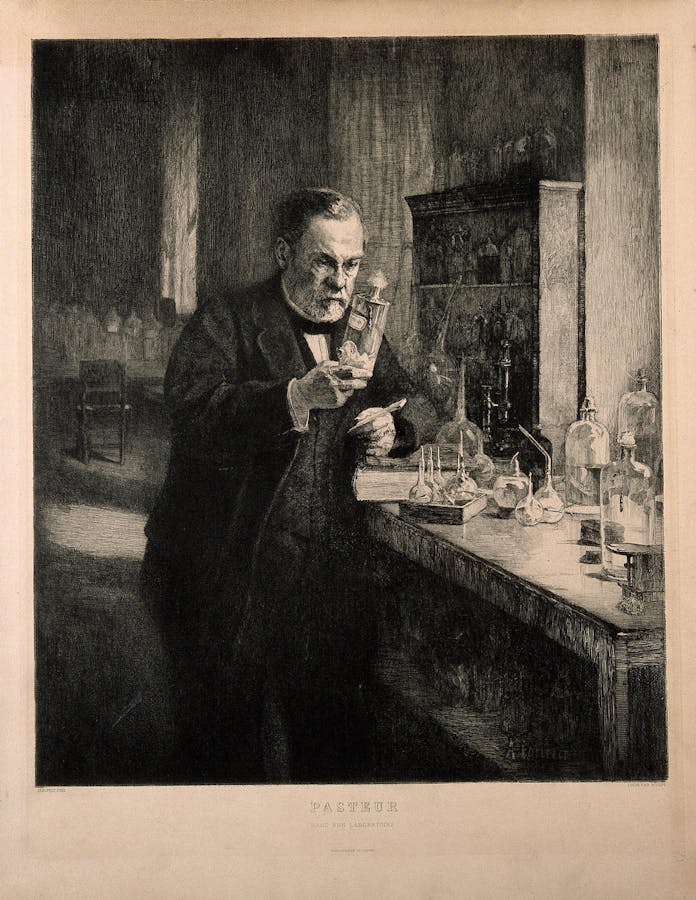

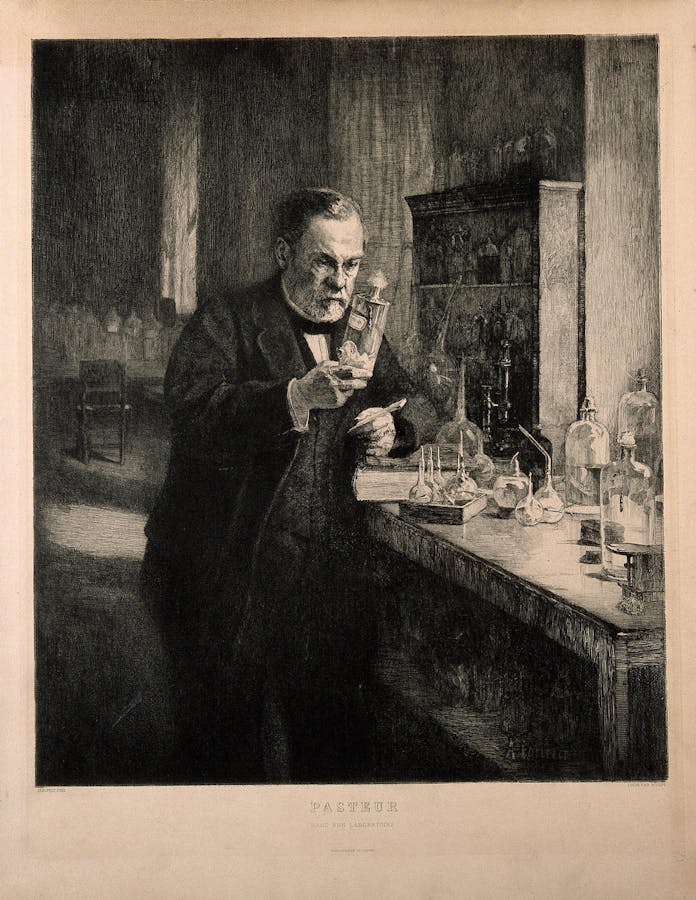

This engraving depicts Louis Pasteur at work in his lab.

Louis Pasteur. Etching by L. Orr after A. G. A. Edelfelt, 1885. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

For centuries, brilliant minds have debated the beginnings of life. Men from different faith backgrounds have tested and refined their ideas, trying to answer the mystery that remains to this day.

In 1686, John Ray, an English naturalist, theologian, and clergyman, proposed the first scientific definition of species. He opposed the idea that life could spontaneously emerge from non-living matter, which he associated with atheistic philosophies.

John Needham was an English naturalist and the first Catholic priest to become a member of the Royal Society. His experiments on boiled mutton broth in the 1740s appeared to contradict Francesco Redi’s findings and lend support to spontaneous generation.

Italian physiologist and Catholic priest Lazzaro Spallanzani made important contributions to the study of animal reproduction. The results of his experiments, published in 1767, called into question Needham’s methods and results, paving the way for Pasteur’s work refuting the old theory of spontaneous generation.

Louis Pasteur seemingly ended the debate about spontaneous generation in 1862. In that year his experiments with microorganisms and sterile broth earned him a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences. Two years later he recounted, “Life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.”

To understand a frog’s reproductive cycle, Lazzaro Spallanzani put pants on male frogs—yes, tiny taffeta pants, according to scholars—and ran experiments. No visual documentation of the frog pants exists, but Spallanzani published several plates such as this.

Dissertations relative to the natural history of animals and vegetables / Translated from the Italian of the Abbé Spallanzani. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s work shed light on the mysteries of animal reproduction. In recent decades, new imaging techniques have provided a remarkable window into the development of new life inside a mother’s body, increasing our awe of the sheer beauty and complexity of human life.

“For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.”

Psalm 139:13–14

Many scientists and scholars today agree that life began from a highly complex process. Our understanding has come a long way since Pasteur, but the quest to understand life’s origin continues.

“The origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.”

Francis Crick, Life Itself, 1981

Can life arise from non-living things, driven by mere chemical reactions?

Until the 1600s, most natural philosophers and theologians assumed that at least some forms of life could “spontaneously generate” from non-living material. Francesco Redi, a Catholic physician and naturalist, challenged the view through a ground-breaking experiment proving maggots came from fly eggs too small to see.

Redi summarized his experiments with the phrase, “All life is from life.” His work ignited a long debate over spontaneous generation that was partially settled by the work of French Catholic chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur.

John Ray, depicted in this portrait, aided in laying the foundations for taxonomy, which is the scientific way of classifying organisms: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species, best remembered as Kevin’s Poor Cow Only Feels Good Sometimes.

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

John Needham’s experiments extended beyond mutton broth. In 1745, his study on blighted wheat revealed microscopic organisms he dubbed “eels,” (figure 6) since they looked similar and appeared to thrive in freshwater.

J. T. Needham, an account of some new microsc. Wellcome Collection.

A portrait of Lazzaro Spallanzani is surrounded by specimens he experimented on, such as the frog, and scientific equipment.

The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

This engraving depicts Louis Pasteur at work in his lab.

Louis Pasteur. Etching by L. Orr after A. G. A. Edelfelt, 1885. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

For centuries, brilliant minds have debated the beginnings of life. Men from different faith backgrounds have tested and refined their ideas, trying to answer the mystery that remains to this day.

In 1686, John Ray, an English naturalist, theologian, and clergyman, proposed the first scientific definition of species. He opposed the idea that life could spontaneously emerge from non-living matter, which he associated with atheistic philosophies.

John Needham was an English naturalist and the first Catholic priest to become a member of the Royal Society. His experiments on boiled mutton broth in the 1740s appeared to contradict Francesco Redi’s findings and lend support to spontaneous generation.

Italian physiologist and Catholic priest Lazzaro Spallanzani made important contributions to the study of animal reproduction. The results of his experiments, published in 1767, called into question Needham’s methods and results, paving the way for Pasteur’s work refuting the old theory of spontaneous generation.

Louis Pasteur seemingly ended the debate about spontaneous generation in 1862. In that year his experiments with microorganisms and sterile broth earned him a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences. Two years later he recounted, “Life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.”

To understand a frog’s reproductive cycle, Lazzaro Spallanzani put pants on male frogs—yes, tiny taffeta pants, according to scholars—and ran experiments. No visual documentation of the frog pants exists, but Spallanzani published several plates such as this.

Dissertations relative to the natural history of animals and vegetables / Translated from the Italian of the Abbé Spallanzani. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s work shed light on the mysteries of animal reproduction. In recent decades, new imaging techniques have provided a remarkable window into the development of new life inside a mother’s body, increasing our awe of the sheer beauty and complexity of human life.

“For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.”

Psalm 139:13–14

Many scientists and scholars today agree that life began from a highly complex process. Our understanding has come a long way since Pasteur, but the quest to understand life’s origin continues.

“The origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.”

Francis Crick, Life Itself, 1981

Can life arise from non-living things, driven by mere chemical reactions?

Until the 1600s, most natural philosophers and theologians assumed that at least some forms of life could “spontaneously generate” from non-living material. Francesco Redi, a Catholic physician and naturalist, challenged the view through a ground-breaking experiment proving maggots came from fly eggs too small to see.

Redi summarized his experiments with the phrase, “All life is from life.” His work ignited a long debate over spontaneous generation that was partially settled by the work of French Catholic chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur.

John Ray, depicted in this portrait, aided in laying the foundations for taxonomy, which is the scientific way of classifying organisms: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species, best remembered as Kevin’s Poor Cow Only Feels Good Sometimes.

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

John Needham’s experiments extended beyond mutton broth. In 1745, his study on blighted wheat revealed microscopic organisms he dubbed “eels,” (figure 6) since they looked similar and appeared to thrive in freshwater.

J. T. Needham, an account of some new microsc. Wellcome Collection.

A portrait of Lazzaro Spallanzani is surrounded by specimens he experimented on, such as the frog, and scientific equipment.

The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

This engraving depicts Louis Pasteur at work in his lab.

Louis Pasteur. Etching by L. Orr after A. G. A. Edelfelt, 1885. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

For centuries, brilliant minds have debated the beginnings of life. Men from different faith backgrounds have tested and refined their ideas, trying to answer the mystery that remains to this day.

In 1686, John Ray, an English naturalist, theologian, and clergyman, proposed the first scientific definition of species. He opposed the idea that life could spontaneously emerge from non-living matter, which he associated with atheistic philosophies.

John Needham was an English naturalist and the first Catholic priest to become a member of the Royal Society. His experiments on boiled mutton broth in the 1740s appeared to contradict Francesco Redi’s findings and lend support to spontaneous generation.

Italian physiologist and Catholic priest Lazzaro Spallanzani made important contributions to the study of animal reproduction. The results of his experiments, published in 1767, called into question Needham’s methods and results, paving the way for Pasteur’s work refuting the old theory of spontaneous generation.

Louis Pasteur seemingly ended the debate about spontaneous generation in 1862. In that year his experiments with microorganisms and sterile broth earned him a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences. Two years later he recounted, “Life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.”

To understand a frog’s reproductive cycle, Lazzaro Spallanzani put pants on male frogs—yes, tiny taffeta pants, according to scholars—and ran experiments. No visual documentation of the frog pants exists, but Spallanzani published several plates such as this.

Dissertations relative to the natural history of animals and vegetables / Translated from the Italian of the Abbé Spallanzani. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s work shed light on the mysteries of animal reproduction. In recent decades, new imaging techniques have provided a remarkable window into the development of new life inside a mother’s body, increasing our awe of the sheer beauty and complexity of human life.

“For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.”

Psalm 139:13–14

Many scientists and scholars today agree that life began from a highly complex process. Our understanding has come a long way since Pasteur, but the quest to understand life’s origin continues.

“The origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.”

Francis Crick, Life Itself, 1981

Can life arise from non-living things, driven by mere chemical reactions?

Until the 1600s, most natural philosophers and theologians assumed that at least some forms of life could “spontaneously generate” from non-living material. Francesco Redi, a Catholic physician and naturalist, challenged the view through a ground-breaking experiment proving maggots came from fly eggs too small to see.

Redi summarized his experiments with the phrase, “All life is from life.” His work ignited a long debate over spontaneous generation that was partially settled by the work of French Catholic chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur.

John Ray, depicted in this portrait, aided in laying the foundations for taxonomy, which is the scientific way of classifying organisms: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species, best remembered as Kevin’s Poor Cow Only Feels Good Sometimes.

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

John Needham’s experiments extended beyond mutton broth. In 1745, his study on blighted wheat revealed microscopic organisms he dubbed “eels,” (figure 6) since they looked similar and appeared to thrive in freshwater.

J. T. Needham, an account of some new microsc. Wellcome Collection.

A portrait of Lazzaro Spallanzani is surrounded by specimens he experimented on, such as the frog, and scientific equipment.

The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

This engraving depicts Louis Pasteur at work in his lab.

Louis Pasteur. Etching by L. Orr after A. G. A. Edelfelt, 1885. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

For centuries, brilliant minds have debated the beginnings of life. Men from different faith backgrounds have tested and refined their ideas, trying to answer the mystery that remains to this day.

In 1686, John Ray, an English naturalist, theologian, and clergyman, proposed the first scientific definition of species. He opposed the idea that life could spontaneously emerge from non-living matter, which he associated with atheistic philosophies.

John Needham was an English naturalist and the first Catholic priest to become a member of the Royal Society. His experiments on boiled mutton broth in the 1740s appeared to contradict Francesco Redi’s findings and lend support to spontaneous generation.

Italian physiologist and Catholic priest Lazzaro Spallanzani made important contributions to the study of animal reproduction. The results of his experiments, published in 1767, called into question Needham’s methods and results, paving the way for Pasteur’s work refuting the old theory of spontaneous generation.

Louis Pasteur seemingly ended the debate about spontaneous generation in 1862. In that year his experiments with microorganisms and sterile broth earned him a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences. Two years later he recounted, “Life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.”

To understand a frog’s reproductive cycle, Lazzaro Spallanzani put pants on male frogs—yes, tiny taffeta pants, according to scholars—and ran experiments. No visual documentation of the frog pants exists, but Spallanzani published several plates such as this.

Dissertations relative to the natural history of animals and vegetables / Translated from the Italian of the Abbé Spallanzani. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s work shed light on the mysteries of animal reproduction. In recent decades, new imaging techniques have provided a remarkable window into the development of new life inside a mother’s body, increasing our awe of the sheer beauty and complexity of human life.

“For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.”

Psalm 139:13–14

Many scientists and scholars today agree that life began from a highly complex process. Our understanding has come a long way since Pasteur, but the quest to understand life’s origin continues.

“The origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.”

Francis Crick, Life Itself, 1981